The Maths and Wheelchair Racing

The first international sports events for disabled athletes held in conjunction with an Olympic Games were in Rome in the summer of 1960. The term Paralympics was only coined four years later at the Tokyo Olympics. At first, wheelchair athletes used conventional heavy wheelchairs (7-18kg) and only contested events up to 200 metres.

The first wheelchair-borne marathon competitor competed in the 1975 Boston Marathon. New races were organised and gradually purpose-built racing chairs appeared. By the 1980s they had become lightweight (4-10kg) and technically sophisticated. The first mile completed in under four minutes by a wheelchair athlete came in 1985 and the roster of Olympic events was considerably extended for both men and women. Intense competition has driven down records in the commonest events on the track and in the marathon, which now features in most top-flight big city races, like London and Boston.

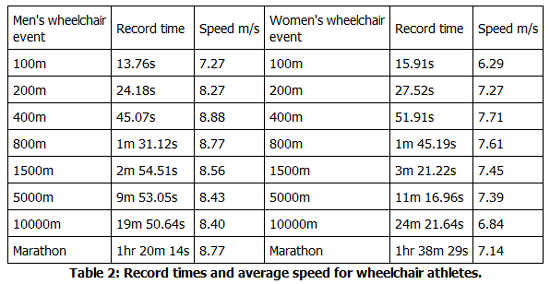

It is very interesting to look at the trends in world record performances for able-bodied and para-athletes. They are both very well defined but quite different. Able-bodied athletes are faster up to about 400 metres but after that their average speed quickly falls behind the wheelchair performances.

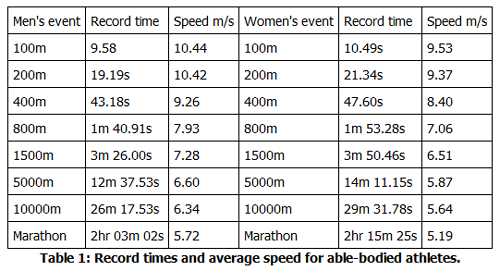

The two tables below show the world record times for the Olympic running and wheelchair events, for both men and women, together with the average speed of the athlete in each case – this is just the distance covered divided by the time recorded. If you like to think of speeds in miles per hour rather than metres per second, then 10m/s corresponds to 22.4mph, so Haile Gebrsellasie cruises around the marathon course at about 12.7mph.

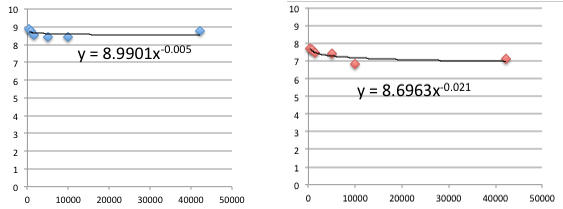

You would expect to find that the average speed of each record run falls as the distance of the event gets longer. For able-bodied running records the trend is remarkably well defined. In the graph below you can see the systematic trends for the men’s and the women’s events. The average speed, U, in m/sec varies as a power of the distance, L, in metres. In other words, U is approximately equal to aLb for some constants a and b Such a relationship is called a power law. The constant a is not that important here as it is just a scaling factor. The interesting quantity is the exponent b. For men this is -0.109 and for women it is -0.111 So U is proportional to L-0.109 for men and to L-0.111 for women.

We can also see from the tables that the average speed achieved during the marathon record is higher than in the shorter distances like the 10000m, and even the 5000m. There are several reasons that contribute to this anomaly. The shorter distance records are set on the track and require the negotiation of two bends on each 400m circuit of the track. Able-bodied runners are not much affected by this but it more problematic for wheelchairs and also harder for them to overtake. This slows the wheelchair on the bends compared with the two straights. The marathon is raced over flat road courses with a minimum of twists and turns and is much better for wheelchair racing although in practice the courses are optimised for the able-bodied runners. Also, wheelchair marathons are more competitive and frequent than 10000m track races and the records are under far more pressure with larger fields of competitive entrants. The tactical nature of 10000m track races also often leads to slower times than in road races.

The unusually small variation of speed with distance also allows wheelchair athletes to be competitive over a far greater range of distances than able-bodied athletes. David Weir has won the London Marathon wheelchair race on four occasions but also has Olympic medals for the 100m, 200m, 400m, 800m, 1500m and 5000m wheelchair events. No able-bodied athlete could ever hope to succeed in more than three of those events. Our average speed analysis shows why it is a possibility for para-athletes.

The fact that wheelchair racers have very similar speeds over the whole range of competitive distances from the sprints to the marathon opens up an exciting possibility for wheelchair athletics. We saw recently that some athletics promoters were very keen on the idea of Usain Bolt racing the new 800m world record holder David Rudisha over the intermediate distance of 400m. In fact, this would not be as interesting as it sounds because Bolt would win very easily, although if the distance was increased to 500m it could get interesting.

Such match ups don’t work well for able-bodied athletes because of the significant differences in speed from one event to the ones on either side of it in distance. However, in wheelchair racing it would be possible to have a super championship featuring the champions and record holders from all the competitive distances over one (or two) intermediate distances.

References:

John Barrow – A version of this article appears in John Barrow’s book 100 Essential Things You Didn’t Know You Didn’t Know About Sport.